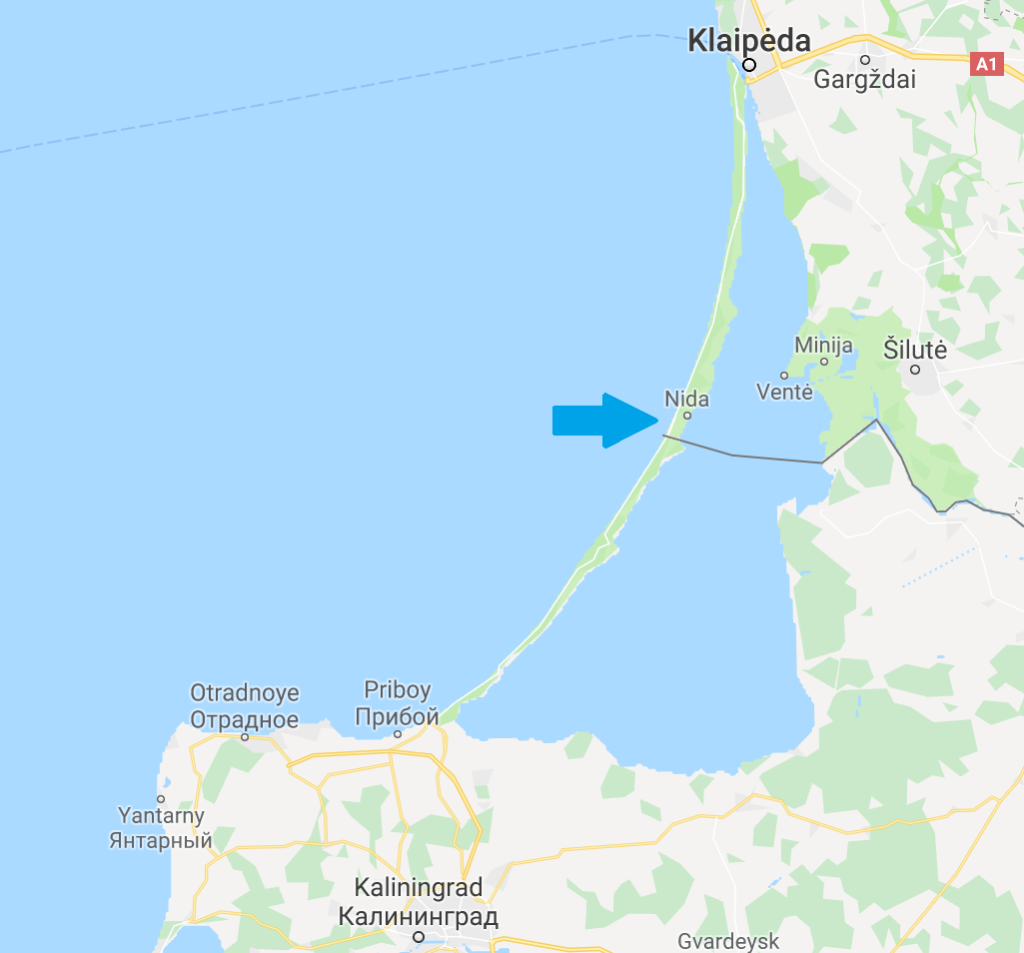

Since my first visit last year, I’ve developed a fascination with the Curonian Spit. The Curonian Spit (German: Kurische Nehrung) is a narrow strip of land separating the Curonian Lagoon from the Baltic Sea, stretching nearly 100km from Kaliningrad in Russia (before 1945: Königsberg) to Klaipėda in Lithuania (before 1923: Memel). These days, the Spit is shared roughly equally between Russia and Lithuania. As with many of the places I visit, however, it once belonged to Germany.

The Curonian Spit has always had a complex history. The ‘indigenous’ population, the Curonians, spoke a Baltic language closer to Latvian than Lithuanian. The Spit has historically been settled by Curonians, Germans, and Lithuanians, and the resulting cultural mix continues to give the Spit its unique character. Even today, the Curonian Spit is largely rural and wild. Most of the Spit is covered in thick pine forests, but its most peculiar feature are its massive sand dunes – the largest in Europe.

In the 1700s and 1800s, widespread deforestation on the Spit led the sand dunes to grow out of control and start swallowing up entire villages – villages that still lay buried under the sand today. The then-Prussian government began a reforestation campaign in the 1800s which succeeded in holding back the so-called ‘wandering dunes’ (Wanderdünen).

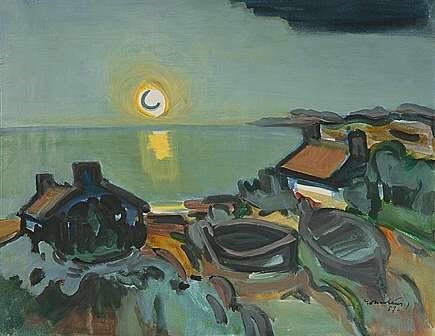

Former fishing villages dot the lagoon side of the Spit. These are made up of traditional wooden houses, often with an intricately carved trim that evokes the shape of Baltic waves, adored with a Lithuanian folk carving at the front – often a pair of crossed horse heads. The trim and window sills are traditionally painted in white and ‘Curonian blue’.

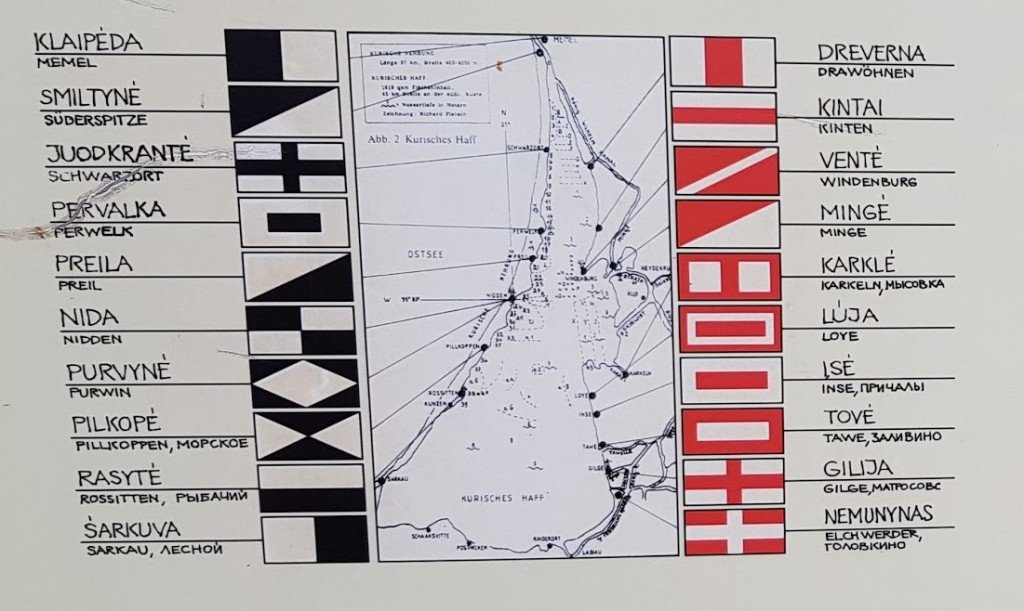

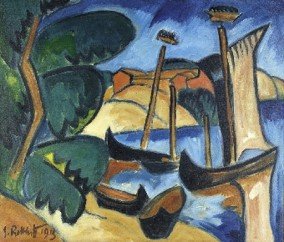

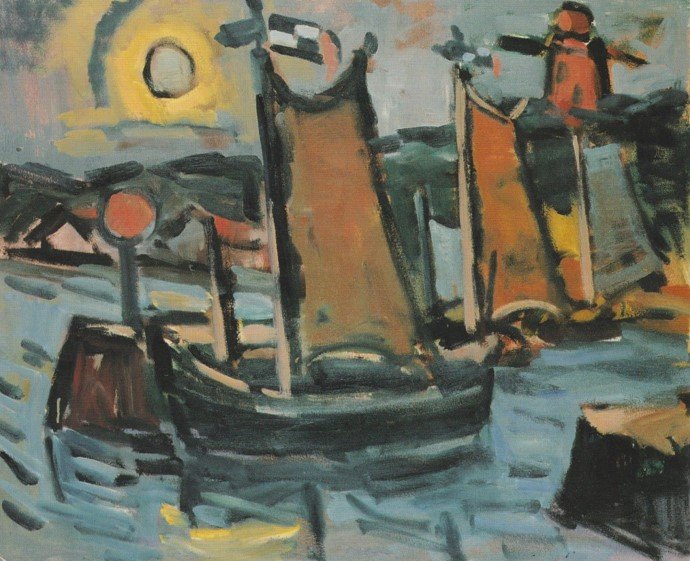

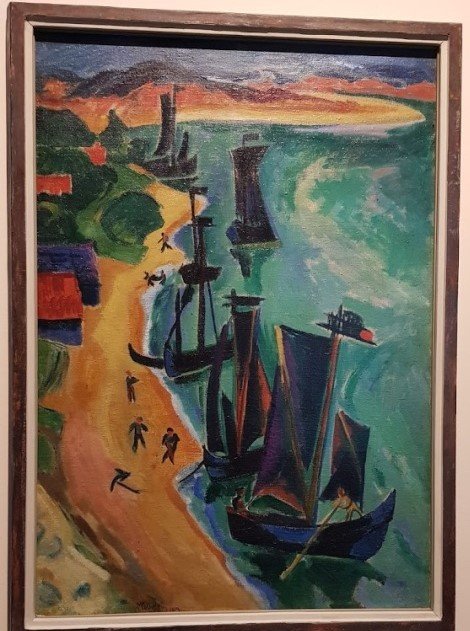

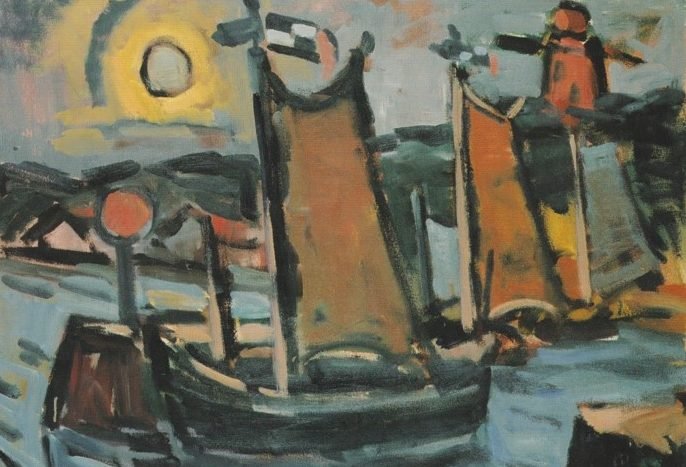

A key defining feature or Wahrzeichen of the Curonian Spit are the Curonian weathervanes (Kurenwimpel) that are ubiquitous on the Lithuanian side of the Spit. These decoratively-carved weathervanes used to sit atop the masts of the traditional flat-bottomed fishing boats of the Curonian Lagoon (Kurenkähne) and acted as a visual code to indicate the boat’s home village.

In order to prevent overfishing in the Curonian Lagoon during the 1800s, the Prussian government divided the lagoon into ‘zones’ and decreed that the Kurenkähne could only fish in their local zones. Each boat had to display the symbol of its home village on its weathervane. Over time, fishermen began to add more and more elaborate wood carvings to their weathervanes, turning them into unique works of art.

These days, there are no traditional Kurenkähne sailing on the Curonian Lagoon today, outside one model rebuilt by an artist in the 1990s that gives daily rides to tourists. But the weathervanes remain as an instantly recognisable symbol of regional identity.

Ever since the mid- to late-1880s, artists from East Prussia and even further afield have been drawn to the Curonian Spit for its beautiful, isolated landscapes, its rural charm, and its unique culture at the intersection of Prussian, Lithuanian, and Curonian folk identities. Most came from the nearby Königsberg Art Academy (Kunstakademie Königsberg). Although artists worked and settled all over the Curonian Spit, most came to stay in the largest village, roughly halfway up the Spit: Nida (German: Nidden).

Even on the Curonian Spit, the natural setting around Nida/Nidden is exceptional. The village is located right at the base of the largest range of sand dunes on the Spit, which are visible from its small harbour. Its traditional fishermens’ houses are surrounded by a pine forest that extends to the Baltic coast on the other side of the Spit, only two kilometres away from the main settlement. On a quiet day in town, it’s often difficult to tell whether the gentle rustling you hear is from the wind in the trees or the waves against the shore, or more likely, a harmony of both.

It’s no surprise then that Nidden gradually developed into what was perhaps the most important German art colony after Worpswede.

The artists who passed through or settled down in Nidden over the long span of the art colony’s existence – from about the mid-1800s to 1945 – were not united in a stylistic sense. Dominant movements within the colony did not evolve so differently from trends in the rest of the German art world. While the earliest artists in Nidden tended to paint in the traditional academic style of the Königsberg Art Academy, the colony began to attract impressionist painters starting in the late 1800s. One of its most famous visitors during this period was the East Prussian painter Lovis Corinth, who along with Max Liebermann was among the most important German impressionist painters. One of his best known works, which hangs today in Munich’s Neue Pinakothek, shows the old fishermen’s cemetery in Nidden with a view over the Curonian Lagoon.

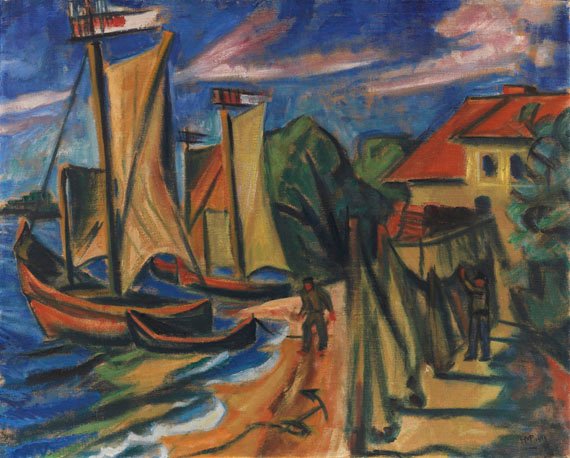

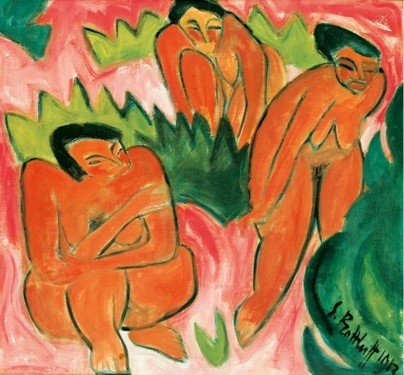

The visits of the Brücke artists Max Pechstein (1909, 1911, 1919; 1939) and Karl Schmidt-Rottluff (1913) caused quite a stir within the community. The expressionist style they brought with them from Berlin was trendy, disruptive, and too outrageous for some of the impressionist painters who had settled there earlier. Despite the indignation of some of the older veterans of the colony, who considered the Brücke painters to be too ‘wild’, expressionism became popular among many of the artists in Nidden. Late expressionism would remain one of the dominant styles there until 1945. This would cause problems later on for the art colony and its denizens when expressionism was declared to be entartete Kunst (degenerate art) by the Nazi government in 1937. But this is jumping ahead.

It would be impossible to talk about the Nidden art colony without mentioning the guesthouse of Hermann Blode. It would not be a stretch to say that without Hermann Blode, there would be no Nidden art colony to discuss. Blode’s guesthouse, established in 1867, was the main gathering point as well as the heart and soul of the Nidden art colony. Blode himself was a great fan of the arts and had developed his guesthouse into an artist’s paradise, including studios and exhibition space.

Most famous of all was Blode’s Künstlerveranda – a veranda overlooking the Curonian Lagoon with walls that were covered in paintings by the many artists who had passed through the guesthouse. Guests would gather on the Künstlerveranda to eat, drink, and debate the latest developments in German and European art late into the night. Not only artists, but also writers, scientists, and other leading intellectual and cultural figures like Thomas Mann and Sigmund Freud came over the years to experience Blode’s famous guesthouse for themselves.

Thomas Mann, in fact, was so struck by the landscape and atmosphere of Nidden that he famously had his own summer house built in a traditional Curonian style on top of the hill behind Blode’s guesthouse in 1931.

„Ich freue mich heute schon wieder auf unseren nächstjährigen Aufenthalt in Nidden. Der eigenartige Charakter dieses Landstriches hat nichts Einschmeichelndes, er ist nicht schön im konzilianten Sinne, aber er kann einem ans Herz wachsen, davon kann ich ein Lied singen und habe es heute versucht.“

Thomas Mann, Mein Sommerhaus (1931)

“I’m already looking forward again to next year’s stay in Nidden. The unique character of this strip of land has nothing ingratiating about it, it is not beautiful in a conciliatory sense, but it can grow on one; I could sing its praises and have tried to do so today.”

Thomas Mann, My Summer House (1931)

Unfortunately, Thomas Mann was only able to spend three summers in his Nidden holiday house before he was forced to flee from the Nazis as a political dissident in 1933. His summer house was turned over to Hermann Blode’s successor, Ernst Mollenhauer, for safekeeping. Mollenhauer would use it to accommodate visiting (and fleeing) artists throughout the 1930s. Thomas Mann himself would never return to Nidden. His youngest daughter Elizabeth would be the only one of the household to come back – and then only in 1992.

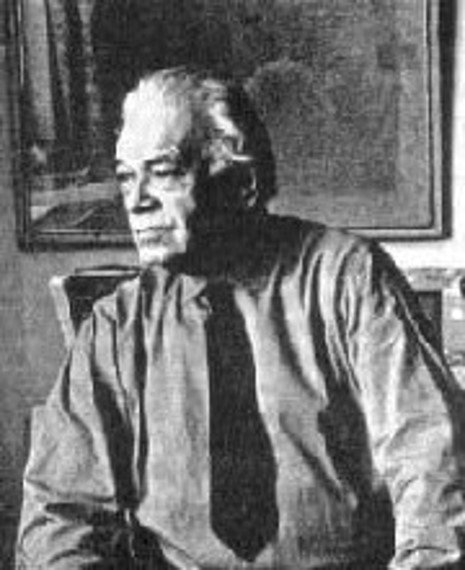

Ernst Mollenhauer, Hermann Blode’s son-in-law and himself a late expressionist painter, had taken over the guesthouse prior to Blode’s death in 1934. Under Mollenhauer’s direction, the guesthouse expanded its support for the arts. It offered new opportunities for young artists, including the Hermann-Blode-Stipendium, which allowed a selected student from the Königsberg Art Academy to receive room and board as well as studio space for the summer in the Blode guesthouse.

Despite the feeling that one can easily get in Nida/Nidden of being far removed from the rest of the world, events in the ‘outside’ world had existential consequences for this little village on the Curonian Spit.

In 1919, as a consequence of the Paris Peace Treaties, the Memelgebiet (Memel region) – which included Nida/Nidden, the northern half of the Curonian Spit, the city of Memel, and the rural Memel delta area – was cut off from Germany. It was turned into an international zone under the administration of the League of Nations, similar to the Free City of Danzig. The Memelgebiet was then annexed by Lithuania in 1923, turning Nidden (now called Nida) into a Lithuanian border town. Tourism from Germany, including the artists who had previously spent their summers in Blode’s guesthouse, suffered under the new border situation.

Ten years later, however, as the Nazis took power in Berlin, Nida’s location just a few kilometres north of the German border briefly turned it into a haven for German exiles, dissidents, and other ‘undesirables’ fleeing the Third Reich. A large number of artists active in Nida around that time belonged to expressionist or other ‘degenerate’ modern art movements. As a result, many of the art colony’s core figures, including Ernst Mollenhauer, had received an exhibition ban (Ausstellungsverbot) or a ban on artistic production (Malverbot) in Germany, cutting off access to their largest market. Still, the colony in Nida remained shielded from the worst of the persecutions on German soil – until Hitler re-annexed the Memelgebiet into the German Reich at the outbreak of World War II in 1939.

Even after the reannexation to Germany, however, the art colony was able to hobble along through the early years of the war, and the idyllic village life in Nida continued almost as normal. This is thanks in part – incredibly – to Hitler’s star architect and Minister of Armaments, Albert Speer, who himself briefly stayed in the Blode guesthouse during the war and was able to prevent East Prussia’s Gauleiter Erich Koch from carrying out his plans to turn the village into a KdF (Strength Through Joy) mass holiday resort.

The civilian population of the Curonian Spit was evacuated in late 1944 and the early winter of 1945 as the Red Army closed in on East Prussia. The Nazi government had denied Mollenhauer the permission to transport the Blode guesthouse’s extensive art collection – as well as the work from his own atelier – out of Nida for safekeeping. With the Russians closing in quickly on the Spit, it had to be left behind. The entirety of the guesthouse’s art collection was burned by the Red Army to heat a sauna they had set up in the occupied guesthouse.

Much of the work produced over the roughly 80 years of the Nidden art colony has therefore been lost for good. The guestbook of the Blode guesthouse, which contained detailed records of the artists and other notable guests who stayed over the years in the colony, was also lost in the ensuring chaos. Identifying which artists or writers were active in Nidden, at what time, and who they might have met or influenced there, remains a challenge for German art historians.

The guesthouse of Hermann Blode is still standing – partially. More than half of the complex, including the gutted Künstlerveranda, was torn down by the Soviet government in the 1960s and replaced by a concrete hotel building. The surviving wings of the original guesthouse still house a hotel with cheap prints in the halls of some of the works produced in the Nidden art colony. An entrance in the courtyard leads to a free, one-room exhibition – opened by Mollenhauer’s daughter Maja in the 1990s – on the history of the Hermann Blode guesthouse and the Nidden art colony.

Surviving works produced at the Nidden art colony are scattered across museums and private collections in Germany and beyond. The largest publicly accessible collections exist at the East Prussia Museum in Lüneberg, Germany, and the Pranas Domsaitis Gallery in Klaipeda (Memel), Lithuania. The Kaliningrad Art Museum in Russia has some pieces, and the Brücke Museum in Berlin holds a number of Nidden paintings and woodcuts by Max Pechstein and Karl Schmidt-Rottluff.

In the back of my mind, I’m always looking for Nidden pieces when I visit German art museums. Given that the colony lasted for about 80 years, there are enough works still out there that the search isn’t entirely in vain. Sometimes I stumble across Nidden paintings in unexpected places, and it’s always a thrill. They’re easy to recognise by sight. The Nidden art colony may not have been united in style, but was united in its landscapes and motifs: the wooden houses with blue and white Curonian trims, the sand dunes, the Kurenkähne, and above all, the Curonian weathervanes. You only need to look to the top of the mast to see that the painting comes from Nidden.

People like me who come to modern Nida looking for traces of the Nidden art colony will find only that: traces. The surviving wings of the Blode guesthouse. Thomas Mann’s summerhouse. Hermann Blode’s grave. Nida is no longer a fishing village but a buzzing resort town with bars, restaurants, and a blue flag beach. Every year it gets more popular with foreign tourists who come – at the root of it – for essentially the same reasons that the artists came before: for its natural beauty, its isolation, its relaxed atmosphere and folk charm. Much has changed, but the Nidden you see in paintings is still there underneath the modern resort… if you squint.

Maja Ehlermann-Mollenhauer, the daughter of Ernst Mollenhauer, herself born and raised in Nidden, perhaps expressed it best:

„Das alte Nidden gibt es nicht mehr, aber seine Künstlerkolonie lebt in der Kunstgeschichte fort und ist dort wohl am besten aufgehoben. Geblieben sind das Grab Hermann Blodes, das Licht über Haff und Meer, das Rauschen des Kiefernwaldes, das Brausen der See und die Erinnerung in den Herzen der Menschen, denen dieses Land Heimat war.“

Maja Ehlermann-Mollenhauer

“The old Nidden no longer exists, but its art colony lives on in art history and perhaps it’s best preserved there. What remains are the grave of Hermann Blode, the light over lagoon and sea, the rustling of the pine forest, the crashing of the waves, and the memory in the hearts of those for whom this was their homeland.”

Maja Ehlermann-Mollenhauer

Sources:

- Jörn Barfod (2009), Nidden: Künstlerkolonie auf der kurischen Nehrung, Verlag Atelier im Bauernhaus

- Museum of Hermann Blode in Nida, Lithuania

- Personal visits in 2018, 2019

Leave a Reply