Berlin is an ugly city.

The most passionate bloggers in this city wouldn’t claim otherwise. Except, perhaps, the Berlin Typography guy. But even so, the strangely pleasing aesthetics of Berlin typography are not ‘beautiful’ in the same way that Parisian storefronts are beautiful, or Tuscan villages are beautiful. Berlin just doesn’t have that charm.

Berliners have no illusions about this. The ugliness of our streets has been elevated beyond the point of a running joke; it’s a statement of fact, mentioned in passing by Berliners in conversation in the same way that you would state any mutually-agreed fact that you wouldn’t seriously expect another person to contradict.

Take Berliner musician Peter Fox’s popular ode to the city, Schwarz zu Blau (Black to Blue), a song and music video about stumbling home at dawn through the streets of Berlin-Kreuzberg, populated with unfriendly characters, vomit, and buses that never arrive. Without a hint of irony, the chorus goes like this:

Guten Morgen Berlin

Du kannst so hässlich sein

So dreckig und grau

Du kannst so schön schrecklich sein…

Good morning Berlin

You can be so ugly

So dirty and grey

You can be so wonderfully dreadful…

An ode to an ugly city if there ever was one.

An interesting point about the aesthetic quality of this city is that it has been both much better, and much worse. Berlin newspapers like the Morgenpost and the Tagesspiegel delight in posting regular features on Berlin ‘damals und heute’ (then and now), ranging from the imperial glory of pre-WWII Berlin to the smouldering ruins of the city centre in 1945 und bleak scenes of war-damaged neighbourhoods divided by the Berlin Wall. In comparison to the latter two, the bland concrete we live in today is a real improvement.

Sometimes, when the concrete looks particularly grey and depressing, it’s hard not to long for a Berlin that doesn’t exist anymore. A Berlin where the area around Hallesches Tor and Belle-Alliance-Platz (now: Mehringplatz) looked like this:

…instead of this:

And indeed, it has never been the beauty of Berlin that has been its primary appeal. Berlin has been many things to many people over the years. A refuge for the French Huguenots during the 16th century. The original sin city of the Weimar era. Capital of Nazi Germany. Symbol of the Iron Curtain, symbol of hope. What it has always been is profoundly interesting. Behind every grim postwar facade is a hidden story about what used to be there and why it’s not there anymore.

Few places in the world are as laden with 20th century history as Berlin, and the city’s modern ugliness is a testament to the forces of that history. Having the will and the interest to look beyond the surface is richly rewarded here. Berlin is a place where you can discover for the first time, after three years, that an unassuming S-Bahn station you pass every day…

…used to look like this:

Or that a big chunk of concrete in the garden colony down the street from your apartment was built by Hitler’s architect Albert Speer as part of abandoned plans to radically reshape Berlin into ‘Welthauptstadt Germania’ (World Capital Germania).

Or that everywhere you go, even the ground beneath your feet tells the story of the people who used to be there – but aren’t there anymore.

As with everything, the Germans have a word for ‘a place you long to be’: der Sehnsuchtsort. The meaning is deeper than simply ‘a place you’d like to go’; Sehnsucht is not a mere want, but a longing or yearning for something. Italy is the traditional Sehnsuchtsort of German art and literature, popularised by Goethe before being taken up in earnest by German Romantic painters.

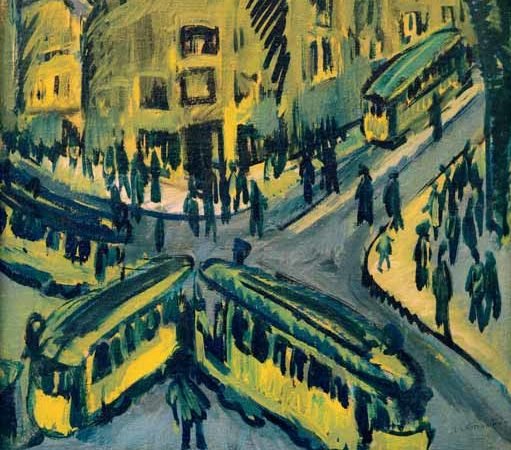

In this sense, Berlin is no Sehnsuchtsort. Its cityscape is not the kind that inspires classical poets. Musicians don’t sing about the beauty of Berlin in the way they have sung about the beauty of Paris or Rome, and surely they never will. In the streets of Paris, French impressionists once painted bright, airy depictions of modern life; in the streets of Berlin, German expressionists painted erratic scenes of urban anxiety.

Berlin isn’t as instantly lovable as the older and less damaged capitals of Europe. Berlin is complicated. It begs you to give it a closer look. Berlin is like the compelling anti-hero in a well-written novel, inviting you to peek beneath its rough exterior, to dig deeper into its complex past, until you realise, ‘Aha, so that’s why you are the way you are.’ Each new chapter and each re-reading of the text tell you something new that you didn’t see before and bring you slightly closer to understanding the bigger picture.

The appeal of Berlin isn’t on display for the world to see. It has to be uncovered, day by day. Bits of history are all around in this city, hiding in plain sight and just waiting for you to find them. If you, like me, have an inclination towards history and an urge to go out and discover it, there’s no place more rewarding than ugly Berlin.

Schreibe einen Kommentar