Some of the best moments as an amateur art-lover are the ones when you first see a new piece, a new artist, or a new movement, and think: ‘Yes, this.’

That was me back in 2012, when I first saw an exhibition on the German expressionist group Die Brücke (1905-13) at – of all places – the Musée de Grenoble. It was about eight months after I’d first come to Europe, and I had yet to realise that I liked art. Although I went straight for the art museums in every city I visited, I hadn’t made the connection yet that this was something I could like. Being ‘into modern art’ felt like something that was for rich, cultured people… not for someone like me.

Still, the expressionist style left a deep impression on me back then. At the time, I was just starting to come out of a long episode of depression. The anxious contours and otherworldly colour schemes of the Brücke artists, but especially of Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, really spoke to my mental state at the time. I felt like I had finally found a branch of modern art that I could emotionally relate to.

Die Brücke mostly fell off my radar for the next few years, until my interest was piqued again in 2016 by a solo exhibition of Kirchner’s work at the Hamburger Bahnhof in Berlin. This exhibition was where I first encountered – or recall encountering – Kirchner’s Berliner Straßenszenen (Berlin Street Scenes), starting with Potsdamer Platz (1913), pictured below.

The Straßenszenen are a set of sketches and paintings produced by Kirchner between 1913 and 1915, i.e. during the period right after the Brücke collective officially dissolved itself in May 1913 due to infighting among its members (chiefly between Kirchner and the others – but that, again, is another story).

The Brücke collective was founded in Dresden but relocated to Berlin in 1911, a move that highlighted and exacerbated significant creative differences within the group. At the time, Berlin was developing at an incredible pace. It was experiencing all the typical problems of a metropolis that was growing too quickly for its own good: urban poverty, prostitution, and an infrastructure straining to accommodate all the newcomers.

As a result, the move to Berlin had a highly polarising effect on the Brücke artists; the group had been heavily inspired early on by primitivist and ethnographic art, after all. Some, such as Karl Schmidt-Rottluff, felt out of their element in the racing pulse of the capital and preferred to retreat to the countryside.

Kirchner, on the other hand, felt both energised and alienated by the relentlessly urban environment of the Großstadt. In channeling those feelings into his art, into the Straßenszenen, he produced not only some of the most notable works of his career but also some of the most famous modern representations of urban anxiety.

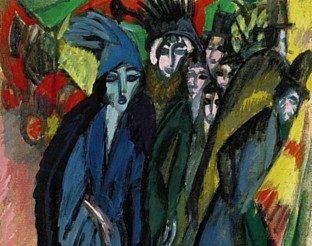

Kirchner’s Straßenszenen, beginning with Fünf Frauen auf der Straße (Five Women on the Street; 1913), portray scenes of urban street life at the turn of the century. The visual style is highly distinctive. Short, nervous brush strokes and an occasionally ‘sickly’ colour scheme convey a uniquely modern sense of anxiety.

The figures that populate the world of the Straßenszenen, largely prostitutes and their clients, are front and centre, sometimes shoved uncomfortably close to the viewer. Their shapes are angular and elongated, skin discoloured, and faces often abstracted to just eyes and cheekbones, making the figures of the Straßenszenen appear as otherworldly creatures of the night. Although they are the subjects of the piece, there is no emotional connection between them and the viewer. The figures appear to either ignore you completely or stare uncomfortably in your direction.

Even though they were created more than a hundred years ago, the Straßenszenen manage to tap into a very particular feeling of urban alienation that is still recognisable today: the feeling of being hopelessly alone in a fast-moving city packed with strangers. A feeling that perhaps anyone who has moved to a new city can understand.

Kirchner himself wrote that the Straßenszenen emerged during ‘one of the loneliest times of my life, when an agonising restlessness drove me out day and night, again and again, into long streets full of people and carriages’. It’s a restlessness that I know well from the loneliest times in my life, too, when I felt compelled to go nowhere in particular to do nothing other than be somewhere else. When you’re lonely, it can feel comforting to just be out among other people – even the otherworldly strangers of the Berlin streets.

It’s oddly soothing to see your own internal struggles reflected in paintings from a hundred years ago. It’s a nice reminder that you’re not alone, that your struggles are normal human struggles, that others have felt how you feel now. In my opinion, it’s one of the best reasons to engage with art and literature.

Schreibe einen Kommentar